Sabbath Day Thoughts — “Limitless Compassion” Luke 13:10-17

Jimmy has spent most of his life feeling invisible. Born with developmental disability and a host of physical issues, he spent most of his childhood in foster care. He attended school, riding in a special bus and learning in special classrooms. Other kids called him names: retard, freak, spazz, dumbo. Nowadays, Jimmy is largely ignored as he stands outside his group home to watch the cars drive past. Eyes look past him as if he isn’t even there.

Heather feels invisible. Every day at lunch she sits in the corner of the cafeteria by herself. She wears outdated hand-me-downs and packs her lunch in a re-used brown paper bag. In gym class, no one picks her for their team. When it’s time for group projects, no one wants to work with her. She sees cliques of friends laughing in the hallways and wishes she were part of that. Eyes look past or around her as if she isn’t even there.

Bert and Jean feel invisible. They had been retired for a number of years when the pandemic forced them to also step back from their civic commitments. Their phone used to ring off the hook. But now, not so much. Many of their friends have passed on. Their kids and grandkids are just so busy. Some weeks, the Meals on Wheels driver is their only conversation partner. They don’t get out much, but when they do, eyes look past or around them as if they aren’t even there.

The world is filled with neighbors who feel alienated, invisible, and alone. You might think that would awaken a mass wave of empathetic outreach, but it doesn’t. Social scientists say our disregard for vulnerable others is a psychological phenomenon known as “compassion collapse.” Dr. Caryl Cameron, director of the Empathy and Moral Psychology Lab at Penn State University, writes that “People tend to feel and act less compassionately for multiple suffering victims than for a single suffering victim…. Precisely when it seems to be needed the most, compassion is felt the least.”

There are reasons for that. We are finite beings with limited resources. We may feel that our action (or inaction) doesn’t make a difference, so we withdraw. Or, we sometimes don’t get involved to protect ourselves. In the face of widespread tragedy and need, it becomes crushing to take on the pain of others. We grow numb and feel powerless.

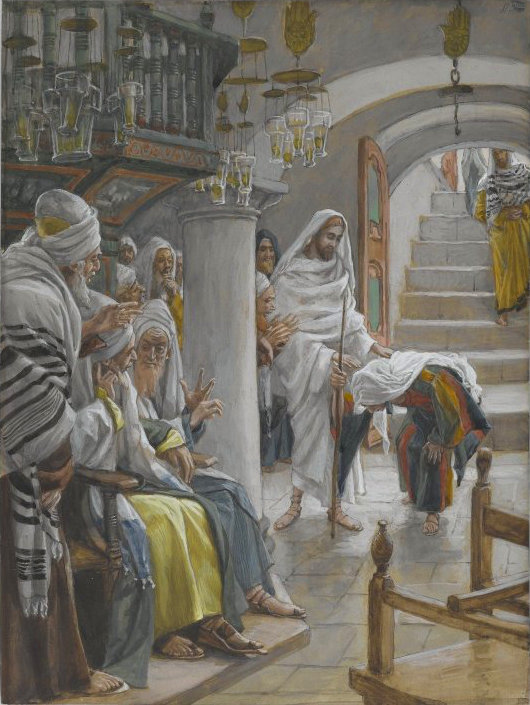

The bent over woman was invisible to her neighbors. She had felt alone and unseen for eighteen years. In the world of the first century, she was a marginalized person—someone who lived outside the community of the righteous because she was physically deformed, spirit-possessed, and a woman. Anyone who has ever had a bad back can imagine the terrible discomfort that she must have felt: muscle spasms; neck pain; difficulty in rising, standing, or walking; the inability to look up and out at the world around her. At some point in her long years of suffering, compassion collapse kicked in for her community. She stopped being a neighbor and simply become the “bent over woman.” She would not have been seated in church on the day that Jesus preached. Instead, she would have been excluded, waiting at the entrance, hoping that someone would see her and speak a kind word into her life of suffering.

Only one person in the synagogue saw the bent over woman. It was Jesus. As only Jesus could, he instantly knew her suffering and need, and his heart went out to her with a limitless compassion that stretched the bounds of what was socially and religiously acceptable in his day. Carolyn Sharp, who teaches Hebrew Bible at Yale, notes that what one could or couldn’t do on the sabbath day was hotly contested in the first century. In fact, the Mishnah Shabbat, a collection of rabbinic teachings, forbade 39 different kinds of labor on the sabbath: sowing fields, baking, building, traveling, and more. It did not forbid healing. In fact, rabbis generally agreed that in life threatening situations, it was acceptable to heal. The rabbis divided, though, over whether healing for non-critical conditions, like being bent over, was permitted.

That’s a long walk to say that Jesus saw the woman and chose to act in controversial, even scandalous, ways. First, he invited her into the sanctuary, into the community of the righteous—to the Moses Seat—where he had been teaching. Then, Jesus did something even more provocative. He laid his hands on her bent over back and raised her up straight, freeing her from the disability that had long held her in bondage. Jesus next concluded his sermon for the day with an interpretation of scripture that silenced the critics. If God would permit a farmer to unbind, water, and feed livestock on the sabbath day, then surely it was permitted to free a woman from the spirit that had long bound her. Jesus gave the bent over woman a proper name, “Daughter of Abraham,” a sister to all the worshipers that day.

The world is filled with invisible people. Like Jimmy, they live with disability. Like Heather, they are friendless school-aged kids. Like Bert and Jean, they are elderly and alone. They are the non-English speaking workers who clean our hotel rooms or pick our crops. They are the economically challenged neighbors who frequent the Food Pantry or collect the empty cans and bottles after rugby weekend. They’d like to be seen, but eyes look past or around them as if they aren’t even there.

Jesus’ scandalous actions in a crowded synagogue one sabbath morning call us to see our invisible neighbors, to welcome them into the heart of the community, to make a caring and healing difference in their lives. Thomas Merton wrote that compassion is the keen awareness of the interdependence of all things. We cannot find wholeness—shalom—apart from community, and communities cannot be whole until the outsider, the excluded, and the marginalized are welcomed, accepted, valued, and included. In a world where some characterize compassion and empathy as weakness, today’s teaching from Jesus is a bold contradiction and a call to action.

Of course, there’s only one problem: compassion collapse. In a world where need can be ubiquitous, our compassion can be overwhelmed. We say, what can one person do in the face of such large-scale pain? We grow numb. We close our eyes. People become invisible. What are we to do?

Peter W. Marty, editor of the Christian Century, says that he builds compassion for those who live in difficult circumstances through the simple practice of imagining what it’s like to walk in their shoes. He does this when he encounters people in daily life who perform jobs that he’s not sure he could manage or tolerate for even a day. Whether it’s an individual enduring dangerous work conditions, tedious assignments, a hostile environment, or depressingly low wages, Marty tries to picture trading his life for theirs. It quickly his alters perspective and shifts his assumptions about how easy or hard life can be for those who undertake hazardous or dispiriting work that often goes unnoticed, work for which we typically feel indifference.

Researchers David DeSteno and Daniel Lim have conducted research to learn how we can have more resilient compassion. Through a series of studies, Lim and DeSteno identified a few factors that enliven our compassion and enhance our capacity to act. It begins with the belief that small steps can make a difference. We can’t solve all the problems of the world, but we can make a simple difference in the life of someone who needs our encouragement and support. It also helps to remember our own experiences of adversity. Remembering our past challenges, suffering, or need motivates us to accompany others. Finally, our personal practice of prayer and meditation can help us to be present to those invisible neighbors. Taking the time to pray and reflect allows us to trust that our actions serve a holy purpose and God is with us. When we are clean out of compassion, we can borrow some of the limitless compassion of Jesus. The world may be filled with invisible people, but it doesn’t have to be. Jesus believes we can make a difference in the lives of those who feel that they are on the outside looking in, longing for care, connection, and community.

This week, we’ll encounter them, those invisible neighbors. They’ll be sitting alone in Stewarts. They’ll be smoking outside their group home. They’ll be struggling to carry groceries to the car. They’ll fear they will miss that important doctor’s appointment because they don’t have a ride.

Let’s open our eyes and hearts. Take the time to see your invisible neighbor. Imagine what it’s like to walk in their shoes. Let’s remember our own experiences of adversity and isolation: that bitter break-up, the boss who bullied us, the health crisis we endured, the time we went broke. Let’s allow those suffering times to awaken our empathy for others and build our resolve to act. Undertake small compassionate acts and trust that they make a difference. Smile. Listen. Share a meal. Offer a ride. Bring someone to church. Finally, let’s ground our action in reflection and prayer. Remember Jesus, who healed a bent-over woman on the sabbath day and continues to long for the wholeness and redemption of our world.

Resources

Jared E. Alcantara. “Commentary on Luke 13:10-17” in Preaching This Week, August 24, 2025. Accessed online at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-21-3/commentary-on-luke-1310-17-6

Jeannine K. Brown. “Commentary on Luke 13:10-17” in Preaching This Week, August 22, 2010. Accessed online at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-21-3/commentary-on-luke-1310-17

Ira Brent Driggers. “Commentary on Luke 13:10-17” in Preaching This Week, August 25, 2019. Accessed online at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-21-3/commentary-on-luke-1310-17-4

Annelise Jolley. “The Paradox of Our Collapsing Compassion” in John Templeton Foundation News, Nov. 20,2024. Accessed online at https://www.templeton.org/news/the-paradox-of-our-collapsing-compassion

Peter W. Marty. “A Failure of Compassion” in The Christian Century, June 2024. Accessed online at https://www.christiancentury.org/first-words/failure-compassion

Carolyn J. Sharp. “Commentary on Luke 13:10-17” in Preaching This Week, August 21, 2022. Accessed online at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/ordinary-21-3/commentary-on-luke-1310-17-5

Luke 13:10-17

10 Now he was teaching in one of the synagogues on the Sabbath. 11 And just then there appeared a woman with a spirit that had crippled her for eighteen years. She was bent over and was quite unable to stand up straight. 12 When Jesus saw her, he called her over and said, “Woman, you are set free from your ailment.” 13 When he laid his hands on her, immediately she stood up straight and began praising God. 14 But the leader of the synagogue, indignant because Jesus had cured on the Sabbath, kept saying to the crowd, “There are six days on which work ought to be done; come on those days and be cured and not on the Sabbath day.” 15 But the Lord answered him and said, “You hypocrites! Does not each of you on the Sabbath untie his ox or his donkey from the manger and lead it to water? 16 And ought not this woman, a daughter of Abraham whom Satan bound for eighteen long years, be set free from this bondage on the Sabbath day?” 17 When he said this, all his opponents were put to shame, and the entire crowd was rejoicing at all the wonderful things being done by him.