Sabbath Day Thoughts — “Come and See” John 1:35-42

Let me tell you a story.

The news swam up the river, all the way from Bethany beyond the Jordan. A prophet came, striding out of the wilderness, his beard grown long, his hair a tangle of knots. His eyes burned and his voice boomed above the muddy waters. He stood knee deep in the Jordan with mixed hope and judgment. The Messiah was coming he promised, with fire and the Holy Spirit. And the urgency of his voice and the conviction of his message had us dreaming of change, of a world free of the Romans and Herod and tax collectors.

So, we, like almost everyone who cared about such things in those days, went to hear him. We paid the hired men to run our boats. We kissed our wives and walked out of the green Galilee and down into the red and brown hills of the wilderness, where the Jordan narrows to a silvery sliver bordered by reeds, north of the Salt Sea. We were baptized by John, and we lingered, listening day after day to his words, so sharp and bold.

When he arrived, we thought he didn’t look like a Messiah, at least no Messiah that we had ever imagined. John embraced him like a kinsman, and the two talked with heads close together, like brothers or children sharing a secret or revolutionaries. As he turned to leave, John said to us, “Behold the lamb of God!” We looked with the greatest of doubts from John to this stranger, who even now was vanishing into the crowd. Then, John nodded at us and shooed us away with a wave of his hand, as if to say, “What are you waiting for?” We looked at one another and shrugged. It couldn’t hurt to look.

We followed at a distance. We noticed that he looked a lot like one of us. He had the strong shoulders of a worker. He wore homespun linen. His face was tanned by the sun. His forearms rippled with muscles that spoke of long years of work, perhaps in a quarry or as a builder. When we edged closer, we could hear that he was humming a folksong.

Beyond the crowd that pressed in around John on the banks of the Jordan, a woman stopped him. She held a listless infant in her arms. Its head lolled. Its eyes were rolling and half-opened. Its face had an unnatural paleness. “Rabbi, Rabbi!” She haled him with a quavering voice. She held her infant out to him like a rag doll. He stopped and took the child, cradling it against his chest. He bounced and swayed from side to side, as a mother soothing a colicky infant would, and he bent his head to whisper into the little one’s ear. Then, he handed the child back and continued his walk.

As we followed him, we heard a disturbance behind us. It was the mother. “Healed” she called out. “My baby is healed.” We turned to see her holding out her child and wondered if it was, in fact, the same baby. Now, its eyes were bright and neck was strong. Within its swaddling clothes, little legs were kicking, as if the infant, too, wanted to join us in following the rabbi.

When we turned back to follow, the rabbi was right behind us. We jumped in alarm, feeling like we had been caught. He looked us over with an appraising gaze, taking our measure, and asked, “What are you looking for?”

What were we looking for? Certainly, we were looking for the Messiah, but these are not words to be lightly spoken; these are words that can make you enemies; these are words that can land you in jail or on a cross. “Rabbi,” we deflected with reddened faces, “Where are you staying?” After all, getting a good look at his shul and his people might be a good idea. He smiled and waved us to walk with him, “Come and see.”

It was a walk. On the way, sitting in the shade of the well where the herdsmen come at daybreak and sunset to water their sheep and goats, we saw an old man. He was a shepherd, long past his prime. His face was as leathery and wrinkled as a Medjul date. His eyes had gone milky-blind from a lifetime spent squinting in the wilderness sun. Lying at his side was a sheepdog, almost as weathered and decrepit-looking as his master. The man’s head swung around in our direction at the sound of our footsteps, and he called out a greeting, “Shalom.”

The rabbi squatted down in the dust next to the man. He listened with kindness to a sad story of aging eyes, lost ability, and long days spent in the shadow of the well until the flocks returned, now guided by much younger men. As the shepherd spoke, this rabbi scrabbled his fingers in the dirt, scooping up the dust. Next, he spat into his hand, more than once, and stirred with his index finger to make a fine paste. “Here, brother,” he said to the man, pressing the paste over his blind eyes and tipping his wrinkled face to the sun. “When it dries,” the rabbi said, “Wash.”

My friend and I looked at one another as if this were the craziest thing we had ever heard, but this rabbi was already striding away from the well. We followed, questioning our every step, but when we were a hundred yards off, we heard the dog barking. We turned and shielded our eyes against the sun. There at the well, the dog was capering like a puppy and the old blind man was shaking the water and mud from his eyes. He looked up and around and began to shout, “Alleluia! Alleluia! I, I can see!” We shook our heads and hustled after the rabbi.

What can we say about where the rabbi was staying? It did not have a scriptorium and ritual baths like the Essenes. It didn’t even have the stone columns and cool interior of a synagogue. Honestly, it really wasn’t even a shul. It was a house, a Beth Ab, the sprawling compound of an extended family of peasants, built around a central courtyard. A shout of welcome summoned the entire household. They surrounded the rabbi, greeting him with kisses and hugs that spoke of great love. As he took a seat in the shade beneath a canopy of palm fronds, we were offered dippers of cool water and fresh bread slathered with yogurt cheese and honey.

A young boy in tears stood before the rabbi and extended his cupped hands. There lay a sparrow, its soft and still cloud of feathers spoke of death. The rabbi took the bird into his hands, held it to his mouth, and puffed the smallest of breaths. When he opened his hands, the bird flew off. This was greeted with gasps of surprise and peals of laughter.

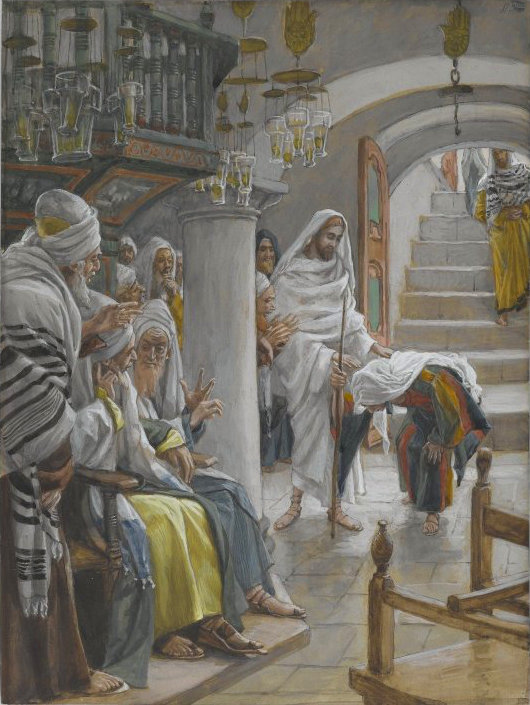

What can I say about his teaching? He didn’t unroll scrolls of the Torah and drone on, like the scribes. He didn’t cite the traditions of the elders, like the Pharisees. He didn’t hold forth, like our old rabbi back in Capernaum. He didn’t address only the men. Women and children, too, gathered at his feet and waited for his words. He told stories, plucking from the world around us holy truths. The birds of the air became a sign of our great worth in God’s sight. A wedding feast became the heavenly kingdom. Seed sown by a farmer reminded us that our ability to hear God’s word is always up to us. My mind came alive and a fire burned in my heart. I wanted him to never stop speaking because every word was somehow drawing me deeper into the mystery of God.

The sun was arcing toward the west when he stood and stretched. The women went off to check their cookpots. The men watered and milked their flocks. The children began to play hide and seek. Our new rabbi looked at us from across the courtyard. He scanned the sky and sniffed the wind, apprising the weather. “Tomorrow, we go north,” he called, “I hear there is a wedding in Cana.” He waved us off, as if knowing that we would soon be back.

As we left the compound, my friend and I looked at one another. His eyes were bright and his cheeks were flushed with the same fire that flamed within me. We did not say it, but we shared one thought. At last, he had come. This was God’s Messiah. If we hurried, we could return to the Jordan, tell our friends, pack our gear, and be back by sunrise. We hiked up our robes and ran with the sun at our backs and our shadows racing before us.

John 1:35-42

35 The next day John again was standing with two of his disciples, 36 and as he watched Jesus walk by he exclaimed, “Look, here is the Lamb of God!” 37 The two disciples heard him say this, and they followed Jesus. 38 When Jesus turned and saw them following, he said to them, “What are you looking for?” They said to him, “Rabbi” (which translated means Teacher), “where are you staying?” 39 He said to them, “Come and see.” They came and saw where he was staying, and they remained with him that day. It was about four o’clock in the afternoon. 40 One of the two who heard John speak and followed him was Andrew, Simon Peter’s brother. 41 He first found his brother Simon and said to him, “We have found the Messiah” (which is translated Anointed). 42 He brought Simon to Jesus, who looked at him and said, “You are Simon son of John. You are to be called Cephas” (which is translated Peter).