Sabbath Day Thoughts — “Repair and Restore” Isaiah 58:1-12

On December 4, 1967, Martin Luther King was in Atlanta for a press conference. Dr. King had come to Georgia to announce his newest initiative in the pursuit of American social justice, The Poor People’s Campaign. In recent years, his activism had taken him north to tackle the problems of racism and poverty endemic in our cities. He chose to live in solidarity with the poor, moving Coretta and their four children to a tiny walk-up apartment in the Lawndale neighborhood on the West-side of Chicago, a community better known by its local nickname “Slumdale.” The entryway of the building where the Kings lived was used as a public toilet, and a hastily applied coat of paint couldn’t hide years of neglect that are the hallmark of low income, substandard housing. In Chicago, while peacefully demonstrating with an interracial group in Marquette Park, Dr. King was hit by a stone, hurled by an anonymous hate-filled hand. He had fewer friends in those days. Malcolm X had rejected his non-violent ethic as too soft and slow to wrest change from white oppressors. One-time white political allies, like LBJ, had come to see King’s radical commitment to the poor and his call for economic change as dangerous. When he stepped up to the microphone that night in Ebenezer Baptist Church, Dr. King looked tired and in need of a friend as he called the nation to “the total, direct, and immediate abolition of poverty.”

Dr. King, in his justice work across the United States, had come to understand that the problem of inequality and injustice is not just about race. It’s about economics. Even as visible lines of color were being crossed and overcome, invisible lines of hopelessness and want kept generations of Americans of all races bound in poverty and need. King saw neighbors “locked inside ghettos of material privation and spiritual debilitation” in urban ghettos, in southern shanties, in rural small towns. Everywhere there was a yawning chasm between prosperity’s children and those for whom the American Dream was unfulfilled, whose lives were defined by hunger, low wages, and substandard housing.

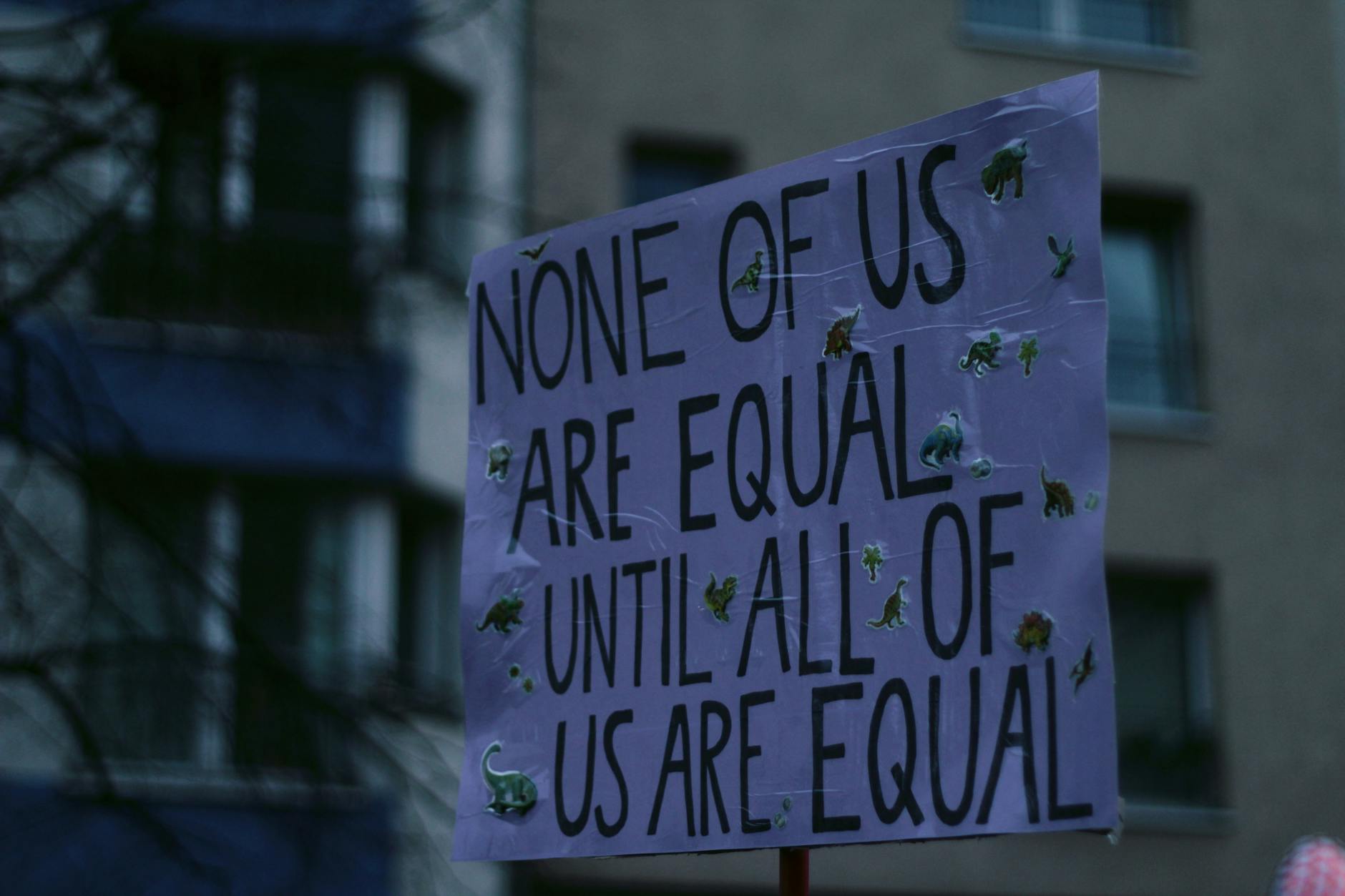

With his Poor People’s Campaign, King resolved to bring Americans together across dividing lines of race to change the plight of the poor. He envisioned a massive, widespread campaign of civil disobedience aimed at the federal government. The poor and disenfranchised of our nation, and those who stood in solidarity with them, would march on Washington, DC, beginning in ten key cities and five rural areas. They would make a cross-country pilgrimage to the very seat of national power. Once there, poor folk would peacefully demonstrate for economic reform by day and camp out in a massive tent city by night. They would stay, as a visible witness to the breach in America’s social fabric, until change was enacted and the promise of dignity was made real for all. Dr. King saw this movement as a direct response to God’s challenge to care for poor and vulnerable neighbors. “It must not be just black people,” King told the press in December 1967, “it must be all poor people. We must include American Indians, Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, and even poor whites.”

The plight of the poor and oppressed is nothing new. In our reading from the Hebrew Bible, God through the prophet Isaiah took Israel to task for their neglect of the poor. “Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?”

Isaiah’s bold words were addressed to good church folks, Israelites who had returned from exile in Babylon. God the great liberator, who had long ago freed the people from Pharaoh’s yoke and led them through the Sinai wilderness into a land flowing with milk and honey, God had again been at work to free Israel from captivity. God had raised up Cyrus of Persia to topple the Babylonian empire and release Israel from bondage. A hurting people had crossed desert sands and through the Jordan’s muddy waters, returning home to their Promised Land. There, they began to repair the walls and repave the streets. Their rebuilding efforts were only outmatched by their piety. They worshipped and fasted, in penance and thanksgiving, seeking to be holy as God is holy.

Yet as God looked at our Israelite ancestors, God saw something terribly wrong with the community. While some in Israel returned from exile to find prosperity and a promising future, others had found only want and privation. God brought liberation to Israel, yet there in the very land meant to be a blessing for all its citizens there was hunger, poverty, and oppression. Children went to bed hungry. Widows had no place to call home. People with disabilities begged in the streets. Despite their fasting and outward signs of piety, the Israelites had missed the point of what it really means to be a faithful people. They could not love God with worship and fasting if they did not love their neighbors, especially their hurting and at-risk neighbors.

Isaiah teaches us that it is only when we choose the fast of righteous living that we can be healed. It is only through care, compassion, and justice that a nation may mend the gaping holes in the fabric of society. It is only by knowing that our well-being is inseparably bound to the well-being of all our neighbors that we begin to understand God’s vision for our world. As long as Israel endured as a land where want co-existed with plenty, the promise of the land would remain unfulfilled. Sabbath day piety must be matched by week day action that feeds the hungry, houses the homeless, clothes the naked, and welcomes all God’s children into the bounty of the Promised Land. It is only then that we become repairers of the breach and restorers of the streets to live in. It is only then that our light shines.

58 years after Dr. King’s insistence that the breach in American society be healed, the chasm between rich and poor gapes wider than ever in our nation. Nowhere is that more apparent than right here in the North Country where multi-million-dollar camps coexist with rusted out trailers, dirt-floored cabins, and substandard, tumble-down housing. In Franklin County, 23% of our children and 13% of our seniors live in poverty. 9,870 people in Franklin County live with food insecurity. That means 9,870 people don’t have the economic resources to put enough food on the table each month to meet their basic nutritional needs. Those numbers do not include the recent cuts to SNAP benefits. Even families who live above the poverty line struggle. 80% of our children are eligible for federal nutrition programs.

We know the two Americas that Dr. King described, and we are challenged today to be repairers of the breach and restorers of the streets to live in. We are needed to stand in solidarity with the poor and oppressed and to share the time, talents, and wealth entrusted to us for the benefit of all God’s children. We may worship God on Sunday, but we also worship God on Monday and Tuesday and Wednesday and more when we reach out to care and make a helping difference in the lives of our at-risk neighbors. We are called to join God’s work of healing and transformation for our community, our nation, and our world.

We will never know how Dr. King’s Poor People’s Campaign would have changed of our nation. One month before the campaign was to be unleashed, five months after that press conference in Atlanta, an assassin’s bullet found Dr. King on the balcony of a Memphis motel, ending his life and cutting the Poor People’s Movement off at the knees. Under the leadership of King’s old friend Ralph Abernethy, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference orchestrated a Poor People’s demonstration in Washington, DC. A tent city, Resurrection City, sprang up on the green lawn of the Lincoln Memorial. But after 40 days and 40 nights of non-violent direct action against a recalcitrant government, the movement crumbled, and the poor returned to their slums and tumble-down cabins, hopeless, silenced, and rejected. Dr. King’s great second phase in the Civil Rights Movement remained unfulfilled. The gap between rich and poor stood as a seemingly irreparable breach.

But the story doesn’t have to end there. Does it? Help and healing are more needed now than perhaps any time since Dr. King stood at the microphone in the Ebenezer Baptist Church. Over the last three and a half decades, the richest 1% of households in the United States have accumulated almost 1,000 times more wealth than the poorest 20% of Americans, and economic inequality is getting worse at a rapid pace. Our nation needs people of faith that love God and stand in solidarity with those who still wait for a seat at prosperity’s table. Are we with Dr. King? Are you with me? May we go forth to be repairers of the breach and restorers of the streets to live in.

Resources

Jonathan Alther, “King’s Final Years,” in Newsweek, Jan. 9, 2006

Josie Cox. “Income Inequality Is Surging In The U.S., New Oxfam Report Shows” in Forbes, Nov. 3, 2025. Accessed online at https://www.forbes.com/sites/josiecox/2025/11/03/income-inequality-is-surging-in-the-us-new-oxfam-report-shows/

Kevin Thurun, “On the Shoulders of King,” an editorial, in The Other Side, Jan-Feb 2003.

Martin Luther King, Jr. The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr., “Press Conference Announcing the Poor People’s Campaign,” Atlanta, GA, Dec. 4, 1967.

Statistics for Franklin County were obtained from Census Reporter and Feeding America online at https://censusreporter.org/profiles/05000US36033-franklin-county-ny/ and https://map.feedingamerica.org/county/2019/overall/new-york/county/franklin

Amy G. Oden. “Commentary on Isaiah 58:1-9a (9b-12)” in Preaching This Week, Feb. 9, 2014. Accessed online at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/fifth-sunday-after-epiphany/commentary-on-isaiah-581-9-10-12

Gregory Cuellar. “Commentary on Isaiah 58:1-9a (9b-12)” in Preaching This Week, Feb. 9, 2014. Accessed online at https://www.workingpreacher.org/commentaries/revised-common-lectionary/fifth-sunday-after-epiphany/commentary-on-isaiah-581-9a-9b-12-2